The current trajectory of students reporting increased feelings of isolation, sadness, and suicidal thoughts is a reversible one. To accomplish this, state leaders, school districts and behavioral health providers must expand on the current framework of school-based mental health (SBMH) to allow for earlier assessment, diagnosis, and treatment across a comprehensive model of care.

Schools are positioned to expand access to care. School resources and systems of support can directly serve students who might otherwise never encounter the healthcare system due to barriers like insurance coverage or transportation challenges. Additionally, studies show school-based care can have profound impacts. A report from the School Mental Health Work Group finds that comprehensive school mental health systems contribute to greater academic success, reduced exclusionary discipline practices, improved school climate and safety, and enhanced social and emotional behavior.

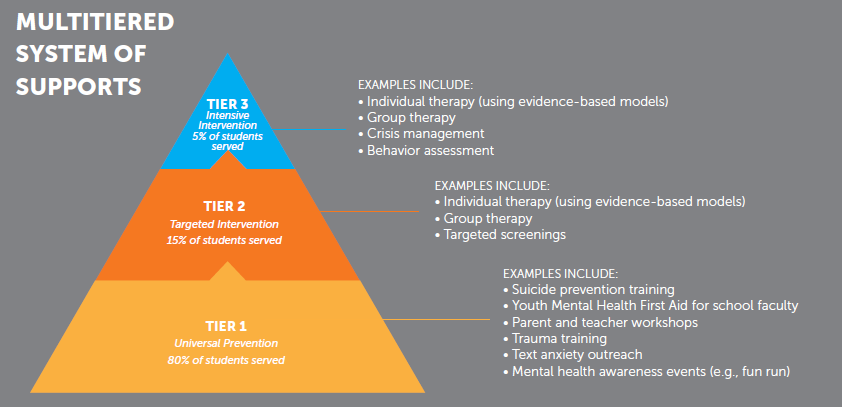

The concept of coordinating evidence-based mental health processes, policies and practices into a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS), similar to those employed in other learning environments, has gained traction across the nation, though the who and how of care delivery may differ depending on the setting.

Source: Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD)

MTSSs for school-based mental health typically share common attributes: At the primary prevention level (Tier 1), schools may implement universal practices to promote mental health and provide early interventions. This could include social-emotional learning programs, mindfulness activities and regular mental health check-ins. These interventions are intended for widespread adoption and aimed at building awareness within the student body.

Tier 2 includes targeted interventions to students who may require additional support. School mental health professionals play critical roles in identifying and assisting students who exhibit signs of mental health difficulties. Collaboration between school staff, families and mental health professionals is key in providing these interventions.

Finally, Tier 3 can involve direct intervention for students requiring specialized support. This includes individual therapy or direct care, or it can encompass referrals to external services or providers for longer term care. While the framework may remain constant, states or school districts can differ drastically on who is delivering the care and what interventions are available, accessible, and affordable for their students.

Internal care model

KFF finds that roughly 68% of public schools have a school- or district-employed licensed mental health professional on staff, and that individual-based interventions were by far the most common form of mental health services offered by public schools in 2021-2022. These school nurses, counselors, or local healthcare staff are uniquely positioned to serve students, especially at the Tier 1 level. “Students often visit the school nurse for physical symptoms, such as a headache or abdominal pain, that might be related to a mental health disorder, such as anxiety, depression, or an eating disorder,” according to Psychiatry Advisor. With the proper training and tools, school nurses and health staff can help surface and support underlying conditions in a setting of trust. Initiatives like awareness trainings, workshops, and screenings are also key to engaging and educating students about their mental health. Internal staff also have proximity to students that can allow them to engage appropriate resources in the community, whether through family interaction, referrals to other providers, or prevention efforts

However, for students with Tier 2 needs and beyond, internal school staff may not have the training necessary for more intensive interventions, or there may be a lack of overall workforce to meet demand across the student population (for the 2022-23 school year, only two states met the recommended ratio of 250:1 of students to school counselors while 17% of high schools overall did not have a counselor). For this reason, many school districts nationally have looked to partner with external providers, either local or national, who can help meet the need.

Outsourced care models

An outsourced telehealth model can be incredibly effective at supplementing capacity. School telehealth partners like Hazel Health, Daybreak Health, and Cartwheel offer an outsourced complement to the existing workforce that can range from direct care, including evaluation and individual or group therapy, to wraparound support, including referrals, case management, and clinical consultations.

This external augmentation can benefit school districts hindered by a lack of local clinicians, such as Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas, as well as schools with a large student body. External models also remove administrative headaches – including licensing, scheduling, and billing – that may burden school systems. And for students and families, telehealth reduces the burden of travel or time away from class while also tailoring care to their specific needs through access to specialists.

However, as strategy and tactics for greater care quality and care capacity have evolved across the nation, several states have moved to create more tightly connected, locally centered, and strategically focused networks of care across their state, integrating schools into the health and mental health ecosystem more fully and formatively.

Integrated care networks

As a pioneer in this model, the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium aims to increase access to care across the state of Texas by bridging gaps in care, increasing the provider workforce, and intervening to support at-risk children and adolescents. As we’ve written before, in 2019 the Texas state legislature took a bold step toward greater mental health access, requiring health systems and government agencies across the state to work together under the leadership of a newly formed Consortium, which now manages five programs, including school-based mental health. The Consortium partnered with Trayt to provide the technology to connect the ecosystem of care across programs, providers, and partners.

While statistics show that just over half of public schools nationally are providing diagnostic mental health assessments and only 42% are providing treatment (with that treatment varying widely in terms of scope and efficacy), Texas’ Tier 3 program goes a step beyond the norm. The Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine or TCHATT, provides telemedicine consults directly to students, referrals to mental health specialists, and coordinated follow-through and care coordination throughout the student’s participation in the program. More than 4 million Texas students can access services through the program, making it one of the largest of its kind nationwide. Trayt’s Measurement Based Care Platform acts as the backbone of this program, giving psychiatrists a 360-degree view of their patients’ health and progress as well as providing clinical leadership with a clear view into outcomes across the program. The success of this patient-centered approach is leading lawmakers to expand funding for the program, bringing care access to any school district in the state that wants it.

Taking note of these successes, law- and policy- makers in other states are exploring similar standardized, intensive, and statewide systems. New Jersey has adopted a similar hub-and-spoke model called the NJ Statewide Student Support Services (NJ4S), while Georgia’s Apex Program promotes collaboration between community mental health providers and schools across the state in a regional MTSS model (workflow outlined here).

However, funding (and relatedly, staffing) remains a barrier to successful and stable programs, and therefore remains a priority for program advocates nationwide.

Funding fuels the momentum

SBMH has received renewed attention at all levels of government, including as a key pillar in President Biden’s Unity Agenda in which the administration committed to doubling the number of school-based mental health professionals.

Accordingly, SBMH funding at all levels of government is racing to catch up to the demand and the need. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been allocated by agencies ranging from CMS to the Department of Education. The Education Commission of the States finds that beyond federal dollars, “states also use funds provided through specific appropriations in the state budget, allocations made through the school funding model and tax revenue earmarked for programs or activities.” Deep-pocketed philanthropists and donors may even have a local or regional impact.

Recurring funding by state can range from appropriations to earmarked revenue, and is typically linked to state budgets and facilitated through Departments of Children and Families, Departments of Mental Health, or similar entities. For instance, Apex in Georgia is funded through the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD) and has grown from a strong proof of concept funded at $634,554 in 2021 to a statewide program bolstered by over $8 million in 2024. Though state policy may lack the speed required to get programs up and running quickly, this recurring funding can be a lifeline to the success and long-term vision of these programs.

However, school leaders can also look at various grant opportunities across the nation as alternative funding mechanisms. The Department of Education’s School-Based Mental Health Services Grant Program provides competitive grants to State educational agencies (SEAs), local educational agencies (LEAs) to increase the number of credentialed mental health services providers in areas of need. The Education Commission of the States takes a detailed look at some of the opportunities and priorities across the country.

It is up to leaders – state, school, policy, and provider – to identify their own mix of goals and capabilities within the context of their states and outline a path toward greater health for their children. By combining an intentional, outcomes-driven model for mental health with funding mechanisms that allow it to operate and scale, these efforts will create a foundation for greater well-being, scholastic achievement, and health outcomes.